When you look for articles dealing with risk management in the supply chain, most of them are all about the “big” disruptions. Earthquakes, hurricanes, sudden economic crises and events of similar magnitude can cause all kinds of problems for a company’s supply chain, like preventing an important supplier from delivering critical parts (example: explosion at Evonik, 2012) or severely damaging the company’s own infrastructure (example: P&G and Hurricane Katrina, 2005). Even seemingly positive events, such as a technological advancement, can pose risk to companies (example: the iPhone leading to Nokia’s downfall as a market leader).

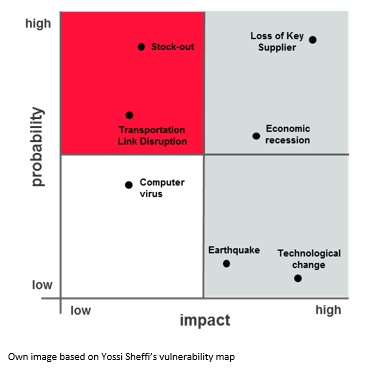

Risk in this context is considered to have a high impact on business, so traditional risk management in the supply chain generally prioritizes scenarios beyond a certain impact threshold (the two grey quadrants to the right in the matrix below). Since it is totally rational to plan for events that have a high probability of occurrence, most companies focus on the upper right quadrant. The lower the probability, the lesser the likelihood of a contingency plan being in place. So some things naturally leave risk managers totally unprepared. The most extreme events are the infamous “black swans”, a term coined by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, describing events which are extremely rare, practically impossible to predict and have a huge consequence.

Below the radar of traditional risk management lies the world of events with a high probability and particularly light consequences (red quadrant). The disruption of a transportation link or a product stock-out are nearly daily business issues for supply chain managers (some say: their justification). The question is: Hurricane, black swan or periodic product stock-outs – what is the bigger risk for your company?

Below the radar of traditional risk management lies the world of events with a high probability and particularly light consequences (red quadrant). The disruption of a transportation link or a product stock-out are nearly daily business issues for supply chain managers (some say: their justification). The question is: Hurricane, black swan or periodic product stock-outs – what is the bigger risk for your company?

Micro-risks become increasingly dangerous

Events with a light impact on the supply chain, let us call them “micro-risks”, are often not a strategic issue for a company, but a problem at the operative level. Rush orders, missing parts, quality defects or machine breakdowns are not always on the risk manager’s agenda. Nevertheless they are dealt with in a similar manner their big disruption cousins: Ad-hoc contingency planning, often referred to as “fire-fighting”, is the chosen weapon. Many companies take such occurrences for granted, since they have a high probability. And they rarely threaten the company as a whole, so they are not considered a “risk” in traditional risk management terms.

It is the dose that makes the poison. The more often these events occur, the more costs they incur. And the modern business world produces them increasingly. Globalized supply chains often produce disruptions which can be felt on the other side of the planet within a day. According to futurologist Magnus Lindkvist, we live in a 22 hour world right now – nearly everything can be moved within that time span, and thus ripple effects along the supply chain are felt almost instantaneously. Fast change and sudden occurrences of disruptions have almost become the one single constant. With the quantity of disruptions increasing, there is also a higher probability that the quantity will pass the impact threshold – and become a “real” risk for the whole company. Built-up micro-risks can become crises.

How to deal with micro-risks

Companies need to find a way to deal with micro-risks. The first step is to accept micro-risks as what they are: events that can be prevented or dampened by planning. The second step is to establish the right counter-measures. But what is the best measure in the case of micro-risks? Most IT systems do not present themselves as a real help here. For example, BI systems can only show you where the current problems are, but not how to solve them. The management of micro-risks not only requires some kind of alert system, but an intelligent solution which delivers concrete options for action. This involves not only playing the digital fire-fighter but preventing problems before they arise. Resiliency is the keyword here.

Resiliency comes in many shapes and sizes. In the context of micro-risks, it means being able to prevent critical events before they occur and not to just waiting and reacting. The positive thing is: This is actually possible because of their high probability and recurrence. Small disruptions are a part of daily operations for companies, and although the particular incident can still come as a surprise, the volume creates general trends that can still be predicted. This calls for intelligent forecast systems, which can calculate the probabilities for disruptions in advance and give planners agile and optimal proposals on how to deal with them.

Conclusion

Companies need to extend their perspective on risk management to include micro-risks in order to achieve real resiliency in times of uncertainty. It does not always have to be a black swan, like a super-volcano swallowing your headquarters (watch out, Silicon Valley!). Many little strokes fell great oaks. Supply Chain Managers should put risk management on their resume (even George Constanza did):

4 comments

Some great points here. It’s important that we continue to look for new ways to look at things like risk management. I think the idea of micro-risks like this will probably catch on – it seems like an interesting perspective.

[…] Source: http://www.inventory-and-supplychain-blog.com […]

[…] When you look for articles dealing with risk management in the supply chain, most of them are all about the “big” disruptions. Earthquakes, hurricanes, sudden economic crises and events of similar … […]

I would like to thank you for the efforts you have put in writing this site.

I really hope to view the same high-grade blog posts from you in the future as well.

In truth, your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my own, personal blog now

😉

Comments are closed.