The hype surrounding artificial intelligence (AI) is now several years old and has hardly subsided. Expectations are huge – but the hoped-for increase in productivity has so far largely failed to materialize in macroeconomic terms. Is the use of the new technology not worth it in reality? The answer lies in a long-term perspective because economists blame this restrained development on the productivity paradox. If the development of AI follows this model, then we will only feel the positive aspects after some delay. An optimistic outlook (in these times of uncertainty) for production and logistics.

What is the productivity paradox?

The productivity paradox describes a historical pattern in which, after the introduction of a new key technology, productivity initially grows only slowly or even collapses, only to grow very strongly a few years later. This was observed, for example, with the introduction of electricity in American factories in the 19th century. Here, productivity stagnated for more than two decades until the new technology made itself felt in strong growth. It was not until engineers changed the layout of production facilities to suit the new possibilities that productivity rose rapidly. The introduction of steam engines – the starting point of the (first) industrial revolution – even led to an actual increase in productivity in the USA only after almost 50 years.

But why does it take so long for a new technology to make itself felt in productivity? Essentially, this has to do with the fact that technology alone does not change anything, but that work itself has to be completely rethought in each case. Process transformations take time and are always accompanied by friction losses. Moreover, these are investments that play practically no role in productivity statistics. Only when the technology is an integral part of the new way of working do the positive effects also become clearly visible.

The development of AI follows the same pattern

The productivity paradox could also be observed in the recent past. In 1987, Nobel Prize winner Robert Solow noted a similar development with regard to the use of computers: “Computers are everywhere – except in the productivity statistics”. Ultimately, the success of computers only became noticeable in the USA, for example, between the years 1995 and 2005.

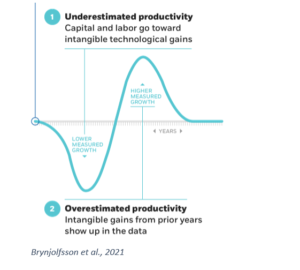

AI also started out with the promise of changing our economy for the long term and of course, ultimately increasing our productivity. But it’s not reflected in worldwide economic growth, even adjusted for pandemics. For a group of researchers at MIT and the University of Chicago, this is no reason to underestimate the impact of AI use: They describe the development as a “Productivity J-Curve”, i.e., a curve that appears as a slightly inclined J in the graph: a short period of stagnant or declining productivity growth is followed by a sharp increase after a short time. And they are convinced that this development will occur faster and to a greater extent with AI than in the past.

AI becomes a success model faster

On the one hand, this is due to the favorable technological environment: breakthroughs in machine learning are coupled with significant improvements in processors and low prices for data storage. Moreover, these possibilities are available even to smaller companies via cloud services.

On the other hand, the Corona pandemic has accelerated global digitization in a way that might have taken companies a full decade in normal times. Who would have thought at the beginning of 2020 that hybrid working would be the new standard for many companies?

A recent survey by the World Economic Forum found that 80 percent of companies plan to accelerate digitization measures and enable more remote working. 50 percent also plan to automate production tasks.

What does this mean for logistics?

The considerations are abstract, and you may wonder what this has to do with logistics. Ultimately, a lot, because productivity is a good indicator of the need for logistics in a globally networked world. And AI has also been a big topic in logistics for a long time, but often just located sometime in the future. Even before the pandemic, many companies were reluctant to invest immediately.

However, introducing AI projects into existing logistics processes is not like switching from a gasoline-powered car to an electric one. As a rule, everyone involved in the process has to adapt to completely new procedures, and that takes time. As a result, the success curve of an AI project can sometimes look like a sloping J, with a slight drop in productivity at the beginning and a steep rise at the end.

The entry into AI for logistics is therefore an important investment for the future. After all, it’s hard to imagine a successful business today that functions without computers – the last great key technology.

Erik Brynjolfsson, one of the researchers who described the “Productivity J-Curve” model, is convinced that we are just leaving the bottom of AI: “I think we’re near the bottom of that J-curve right now and we’re about to see the takeoff.”

References

Brynjolfsson, Erik, Daniel Rock, and Chad Syverson. 2021. “The Productivity J-Curve: How Intangibles Complement General Purpose Technologies.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 13 (1): 333-72.